If you are a medical student who has decided on a career in family medicine, you will need to weigh your residency program options carefully — the right choice may not be the obvious one. Program location, ranking, educational rigor, opportunities to specialize, and other factors will affect your future, so you must consider all facets thoughtfully. We’ll discuss several important components of choosing a family medicine residency program in this post, but first, here are several useful resources from the AAFP to get you started:

- Download — and read cover to cover — the free comprehensive guide by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), Strolling Through the Match.

- Register with the American Medical Association’s FREIDA Online® database service, which enables you to search and access information on some 9800 ACGME-accredited graduate medical education programs and more than 100 combined specialty programs. FREIDA Online® enables clear comparisons of multiple programs and, for AMA members, a dashboard feature empowers residency candidates to rate, track, and manage programs to which they are interested in applying.

- Plan to attend the AAFP’s National Conference, which is held each summer in Kansas City and provides a cost- and time-effective opportunity to touch base with hundreds of family medicine residency programs all in one place.

There are an abundance of helpful online resources to assist imminent med-school graduates in navigating the complex — and rather grueling — Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) and National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) processes. Here are some of the bigger, more nuanced aspects of evaluating family medicine residency programs.

Likelihood of Being Matched to a Family Medicine Residency Program

According to statistics published by the NRMP and reported by the AAFP, some 3060 graduating medical students chose careers in family medicine in 2015, representing a sixth consecutive year of growth for the field. At the same time, some 3216 family medicine residency positions were offered, meaning 95.1% of available positions were filled. While the fill rate in 2015 was down slightly from 2014, there was an absolute increase of 84 positions, with some 60 additional medical graduates accepting positions in family medicine residency in 2015 compared with last year.

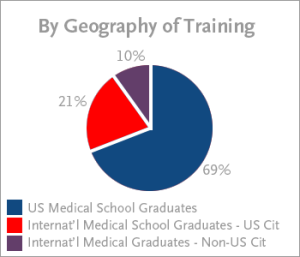

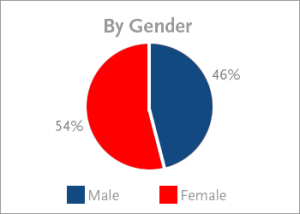

In July 2014, the AAFP reported that 477 accredited family medicine residency programs hosted a grand total of 10,662 first through third-year residents:

Growth in the number of U.S. medical school graduates choosing family medicine slowed at an unexpected rate in 2015, totaling 1422, with only six additional U.S. medical school graduates selecting family medicine compared with the total number of U.S. students in 2014. With some 2.3 family medicine residency positions available per interested U.S. medical school graduate, most U.S. students with solid academic records can expect to be matched to programs that suit both their needs and career aspirations.

Finding the Program For You

There is no U.S. News & World Report-style ranking of family medicine residency programs to use as a starting point in program search. Indeed, it would be nearly impossible to produce such a report because there are far too many personal variables involved in evaluating family medicine residency programs. Your first round of selections — where to apply and interview — will likely depend on answers to such questions as:

- Where you want to live

- What type of community you wish to serve — urban, suburban, rural, underserved, or military

- Whether you are interested in pursuing a combined specialty — such as combining family medicine with emergency medicine, obstetrics, psychiatry, or preventive medicine

Ranking prospective family medicine residency programs for the match will rely on a much more comprehensive list of decision factors. Indeed, an evaluation guide offered as part of the AAFP’s Strolling Through the Match publication includes some 60 program attributes to consider scoring as you progress through the interview process.

While we can’t cover every point of consideration in detail here, we will attempt to address major buckets into which most of the key program attributes sort.

Educational Rigor and Value

Consider the following factors related to programs’ educational rigor, breadth, and overall value:

- Program accreditation and philosophy

- Rotations

- Rounds

- Conferences and seminars

- Faculty dedication to teaching (vs. research and other professional obligations)

- Elective opportunities

- Exposure to subspecialties

- Variety of clinical settings

- Libraries and other resources available to residents

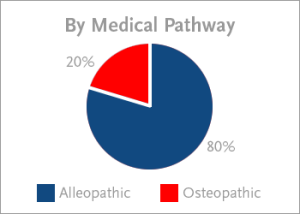

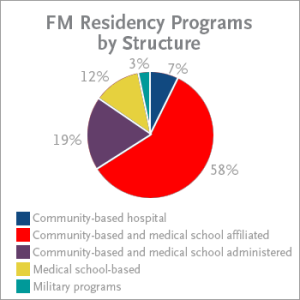

Different program structures may yield dramatically different educational experiences, though how you value those experiences is entirely subjective and often a function of where and how you hope to practice medicine. The latest available statistics for family medicine residency program structure (as of July 2013 and reported by AAFP) are as follows:

While you might assume programs affiliated, administered, or run by medical schools to be more educationally rigorous or diverse, this is not always the case. Medical school faculty may be spread too thinly or have multiple competing obligations, such as research pursuits taking their attention away from teaching residents.

At the other end of the spectrum, community-based hospital residency programs may find it challenging to consistently deliver relevant, high-quality seminars and lectures. Community affiliate programs may also present serious logistical difficulties for residents who are forced to travel – on tight schedules – to take part in mandated lecture, conference, and seminar activities at secondary locations.

If you are evaluating unaffiliated community-based hospital residencies, it will be important to ascertain the commitment of staff physicians to supporting the program. Other decision factors may include:

- Opportunities for interprofessional collaboration with nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dieticians, physiotherapists, social workers, and mental health therapists

- Proportion of education versus so-called scut work

- Board certification rates of program graduates, which can be investigated online

Either way, it is exceptionally important both to define what you want from future practice and — in that context only — gain full understanding of potential educational value in each program. Those conducting official interviews will try to sell their programs to you as a candidate, so it is also important to seek out and talk with people who have gone through your prospective programs in the recent past, preferably under incumbent program leadership.

Competing Specialties May Influence What You Learn and Don’t Learn

A huge decision factor for family medicine residency applicants will be whether to enter a program that is “opposed” or “unopposed” by other medical specialties. With finite numbers of cases in given time periods, each medical institution must allocate cases and opportunities to learn and practice specific medical procedures. That allocation can be biased in favor of competing specialties, such as internal or emergency medicine, especially with respect to procedures that PCPs will rarely (if ever) be expected to perform in clinical practice.

Although family medicine residents working in opposed programs sometimes report being treated as second-class citizens, they also appreciate the greater diversity of academic content and opportunities to interact regularly with residents in other specialties. By contrast, those entering unopposed family medicine residency programs often say they receive greater personal attention from faculty, but — because they are the only residents available — may end up doing rotations and procedures that fall outside their areas of interest.

Where you intend to practice medicine over the longer term will be a key factor in deciding between opposed and unopposed programs. For example, a medical student intending to practice family medicine in an isolated rural setting might opt to complete residency in an unopposed, busy urban setting that will expose him or her to the greatest possible variety of patients, cases, clinical diagnoses, and procedures in preparation for practicing in relative isolation. If, on the other hand, a student is aiming to work long-term in a large, suburban primary care practice with ample opportunities to consult with other physicians and specialists, he or she might be content to train in an opposed program that emphasizes skills related to preventive care and patient interaction versus procedures they are unlikely to ever undertake.

Program Competitiveness and Reputation

Former residents’ online reviews of family medicine residency programs can be quite interesting and instructive to read, but you should view them with some caution. Some may be years old and, therefore, not reflective of current program leadership and structure. While some negative reviews may be perfectly valid and worth investigating further, others may be just sour grapes in a world where it is altogether too easy to take to the internet with anonymous comments.

Additionally, because this is a field with more open positions than candidates, some family medicine residency programs will choose to fill openings with foreign students (non-U.S. citizens attending non-U.S. medical schools) or international students (U.S. citizens attending medical school abroad). You may find undertones of prejudice against the competitiveness of these programs in online reviews, but you should look past such simplistic assessments because U.S. family medicine residency programs often attract top students from highly rigorous foreign medical schools, and these students bring welcome diversity in terms of medical knowledge and sensitivity to cultural nuances in patient populations, as well as many other benefits that can enrich your training.

It is far better to spend time conversing with acting residents as well as recent program alumni before making snap judgments about program competitiveness and reputation. When traveling for interviews, try to make contact with program alumni who are not part of the official interview team. Other people to check in with around program competitiveness and reputation include your own medical school faculty and physicians working in desired practice settings.

Personal Happiness

Factors bearing on personal happiness — work hours, call schedules, patient loads, salary vs. cost of living, perks, benefits, surrounding community, and so forth may have less influence than academics on your ultimate competence as a primary care physician. Nonetheless, they still need to be incorporated into any balanced rating or scorecard system to assist with ranking family medicine residency programs comprehensively for the match.

Ranking Your Options

Medical students going into family medicine residencies should develop their own proprietary weighted models for scoring programs across a uniform set of criteria. This will allow you to draw clear comparisons and note winners and losers for match-ranking purposes. This weighting will be subjective as each person and each family values different things. While location may matter strongly to one, breadth of training may matter greatly to another. You will need deep introspection and honesty to develop the best personal model for you.

Regardless of how competitive a program may seem and where you place your own chances of being matched, always rank your preferred programs first. While the matching algorithm is complex (and a bit mysterious), it is known that student rankings of programs always prevail over program rankings of students. This means there is always a possibility that even highly competitive family medicine residency programs will not fill all open positions with their top-ranked student choices. Because total positions outnumber student applicants in family medicine, you always have a chance of matching to a preferred program.

At the same time, the match is a contractually binding process, so, while it is important to rank enough programs to improve your probability of matching, never rank a program you definitely do not want. If, as in rare cases, you do not match, you may still be able to scramble into a program that falls lower on your ranked list.

Here are some additional recommendations to get you started as you explore the family medicine residency program options:

Excellent information but I think it has one important omission – children and grandparents. Residents with children have stresses that residents without children do not. (Joys too, but that’s not germane to the discussion.) Grandparents of their children, if they live in a town with a residency program, can provide very important assistance with child care, removing this stress to a significant degree. I think grandparents are so important that if I were the resident, I would rank an average residency in the city where my child’s grandparents live higher that a better residency in a city where I had no family. Learning depends more on the learner than the teacher. A less-stressed out resident will learn more and perform better than one who is shouldering the entire child care burden.

Hey Bryan Burke,

I agree. I’m glad I scrolled down to the comments section. I am in the dilemma of ranking right now, and really like this community program near my parents so that I can start a family sooner…versus going to a prestigious residency in a city in which my husband and I have no family what so ever. Then again, it doesn’t matter where you do residency unless you want a fellowship.

Also, an attending told me it is important where you do residency bc you most likely will settle in that area.

[…] NEJM’s Advice on Choosing a Residency delves into the un/opposed topic really well, too. Check it out!

My ranking order will definitely depend heavily on proximity to grandparents, cost of living, and even on site child care. I can be most productive and learn best when I know all is well at home. I am curious to know how others in similar situations handled the question “Why our program?” Obviously I would address other preferences first (unopposed programs, longer ob and peds rotations, etc) but it will be hard to pretend that there isn’t more to the story. I have heard program directors cannot ask if we have family; this seems to imply that family is off limits during an interview.

“Because total positions outnumber student applicants in family medicine, you always have a chance of matching to a preferred program.”

This article was written in 2015…is this really true? I doubt it.

If positions outnumbered the applicants, then why do we have so many go unmatched every year?