It’s 7:30 AM, and in thousands of doctors’ offices around the country, family physicians fling wide their doors to the first patients of the day. Family practice medicine provides primary care for the entire lifespan — unlike internal medicine and pediatrics, the other two specialties that make up the universe of primary care in the United States.

Family practices see insured and uninsured patients, children, adolescents, the elderly, middle-aged men with diabetes, women hoping to become pregnant, depressed patients, veterans, and every other type of person you can imagine.

According to the CDC, in 2010, more than a billion people in the United States visited a physician in an ambulatory care clinic. Of these, 55.5% were primary care physician visits. Family doctors saw 44% of these patients. In short, primary care, especially family medicine, is the backbone of the U.S. health care system.

What Is Family Practice Medicine?

Family practice medical schools and residency programs emphasize caring for patients of all ages in the community setting and being a hub for all the medical care a patient may be receiving. The American Academy of Family Practice (AAFP) explains:

Unlike pediatricians, who only provide care for children, and internists, who only provide care for adults, family medicine encompasses all ages, sexes, each organ system, and every disease entity. Family physicians also pay special attention to their patients’ lives within the context of family and the community. While there are similarities between family medicine and the other primary care specialties, family physicians have an unprecedented opportunity to have an impact on the health of an individual patient over that person’s entire lifetime.

Trends in Family Practice Medicine

Family doctors tend to hang their shingles in rural and poor areas in the United States, but their numbers are decreasing. According to the AAFP census, the Mountain, West North Central, and Pacific regions of the United States have the highest percentage of MD graduates (13.5%, 12.3%, and 11.4%, respectively) entering family medicine. However, the AAFP census also reports a decline in these numbers. Children in rural and underserved areas depend on family physicians more than ever for health care, but “fewer than 20 percent of AAFP members practice in rural areas, down from 31.7 percent in 1994.”

Family physicians are increasingly leaving private practice for hospital- and HMO-based facilities. According to a survey reported by the AAFP, “residents today …would rather earn a paycheck initially than assume the financial risk of practice ownership.”

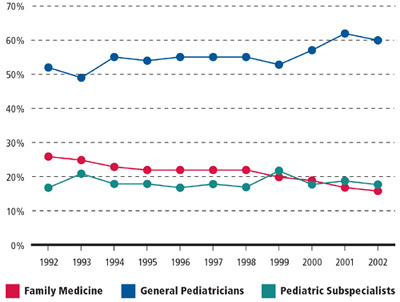

Fewer family physicians are seeing pediatric patients now than they used to. The proportion of children’s health care being provided by family physicians has declined significantly over the past two decades. The AAFP reports that the “share of children’s health care provided by family physicians and general practitioners decreased by about 33 percent between 1992 and 2002, from one in four children’s visits to one in six.”

Percentage of Children’s Office Visits, by Specialty

Fewer family physicians are seeing pregnant women and delivering babies than in the past. According to the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), fewer than 1 in 10 family physicians are providing maternity care. The AAFP predicts that “these numbers likely will continue to decline as more of us take employed positions.”

Conflicts in Family Practice Medicine

Hospital privileges for family physicians used to be taken for granted when “medical doctor” meant one thing: family practice. For quite some time now, however, family physicians have had to fight local turf battles over hospital privileges with internists, pediatricians, and obstetrician/gynecologists.

A recent AAFP member survey showed that fewer than 20% of AAFP members have hospital privileges for routine obstetric delivery, and fewer than 60% have privileges for newborn care. Those numbers are down from 25.7% and 64.7%, respectively, in 1995.

A doctor in Texas, Dr. Jeff Alling, made national news in 2013 when he fought for his right to perform maternity care at Wise Regional Health System in Decatur. According to the New York Times:

That hospital, where Dr. Alling delivered babies before he left for Bridgeport, instituted a policy in 2009 that allowed physicians to deliver babies only if they had undergone a three-year residency program specializing in obstetrics and gynecology.…

As a result, Dr. Alling and three other family physicians were denied obstetrics privileges at Wise Regional and are in legal mediation with the hospital. They estimate that 50 to 100 pregnant patients, the majority of whom live in rural areas and are covered by Medicaid, have been affected by Wise Regional’s refusal to grant them obstetrics privileges. Those patients now have three options: they could transfer their care to one of three doctors with obstetrics privileges at Wise Regional; continue to see their current doctor and go to the emergency room when they are in labor; or travel roughly 30 miles to Jacksboro, where a community hospital has granted those family doctors obstetrics privileges.

An article in Family Practice Management titled “Fighting for Hospital Privileges” explains the origins of conflicts over hospital privileges, which include:

- hospital departments of family medicine that are not fully staffed

- one set of criteria for family physicians and another for internists

- hospitals requiring approval by other departments for FM privileges

- physicians in other hospital departments refusing to consult with family physicians

The article provides advice and protocols for family doctors to follow in order to avoid, negotiate, and (if necessary) fight conflicts over privileges. Key points include preempting the battle, documenting your credentials, and resolving the conflict at the hospital:

Your hospital should provide a full clinical department of family medicine that functions in exactly the same manner as any other department in the hospital and has full credentialing authority.

Before you fight a privileging battle, be sure you can document your training and experience performing the procedure in question and become familiar with your hospital’s hearing rules and procedures.

Privileging is a local issue solved best through professional and collegial discussions at the hospital level.

Board Certification for Family Physicians

Originally established by American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the Maintenance of Certification (MC-FP) process is intended to create a framework for physicians to follow, to establish standards, and to maintain accountability in the field of medicine. The MC-FP process encompasses initial certification as well as recertification under the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM).

The American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) certification/recertification process includes the following four components:

- Proof of holding a full and unrestricted medical license

- Completing sets of self-assessment modules (SAM) and earning continuing medical education (CME) credits

- The ABFM exam

- Systematically measuring continuous improvement of patient care in daily practice

Although it’s buried at step 3 of the above list, studying for and passing the ABFM exam is a rite of passage for family physicians — many of whom are required by insurance, hospital rules, and other regulatory bodies to keep up their board certification.

“I think the best thing to enhance confidence before taking a high-stakes test is knowing that you have executed a well-designed study plan and that you are prepared,” says Dr. Mark Nadeau, senior reviewer of NEJM Knowledge+ Family Medicine Board Review and a clinical professor and residency director in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

Dr. Nadeau suggests looking first at your own practice. You will most likely not need to study the conditions and problems that you see most often, especially if you keep up with and review the most recent guidelines in these areas. But even the busiest family physician is unlikely to encounter the full breadth of the specialty over the course of a year or two. So your study plan needs to reflect the full ABFM exam blueprint, to be sure you can answer questions relating to scenarios you see less frequently, like obstetrics and pediatrics, for example.

Family practice medicine is currently the only specialty providing primary care to patients across the lifespan. The wide swath of knowledge these physicians need to know and keep up-to-date in order to diagnose, test, and treat patients of all ages and all conditions is truly remarkable. It’s important to remember that for many people relying on government aid and living in rural areas, the family doctor is the closest and most reliable option. And although many doctors choose to specialize, some prefer general medicine for its variety and challenge. In a world of constant change, some patients, too, prefer to see the same doctor from childhood through adolescence and adulthood and into old age.

More on family practice medicine from NEJM Knowledge+ and the Learning+ blog:

Simplifying MOC for Family Physicians: The TRADEMaRQ Study

I wonder if family physicians in the US are already facing this challenges of being schemed out of hospital privileges, what does the future of the family practice holds in many other nations looking unto America as the standard.

The need for family physician will continue as the health system continue to develop reaching a stage where prohibitive cost and delay in seeing the super-specialist will limit the provision of basic and affordable care needed by the majority of the population.

Wisdom demand that we continue to keep the santity of family practice because of the several benefits it provides for the growing population of the world.

It’s cool to see that there are medical schools that have programs that are specifically designed to help medical students prepare to take care of people of all ages. It’s comforting to know that there are services like this that are dedicated to helping people live better lives and to keep them healthy. I’m grateful for people who dedicate themselves to helping people have better lives.

Family doctors seem to develop more of a personal relationship with their patients seeing that they can care for someone over their lifespan. I’m sure that leads to more confidence between patients and their doctors. I too and grateful for those who dedicate their lives to helping others.

My cousin is trying to figure out what to study at the university. It was interesting to learn that family medicine can help to treat children sicknesses and illnesses. I hope this article can help us to know what career will be best for my cousin.

I just moved to a new area and I am trying to figure out what health clinic and doctor I should go to. I am happy that you pointed out that a family doctor would treat you for life. That would be really comforting for me because I am a pretty shy person.

I’ve heard the term family practice before, but I had just kind of blew it off in the past before I had kids. Now that I’ve got a family of my own, being able to understand what this particular practice is would be helpful. I’m glad that you included an excerpt from the AAFP, and how you explained that family practice medicine treats everyone, regardless of age and sex. I’m going to have to see if we can find a good family practice that I could have as a go to for my wife and kids, and be able to know we can get quality treatment!

It’s good to know that family practice medicine is now becoming more and more common within the community. I like the fact you mentioned that they are able to offer various specializations in the different fields of medicine. I would strongly recommend this to my friends and family. Thanks.

It is essential that all individuals, whether healthy or ill, need to have their own doctor that practices family medicine. Accordance to our observations, family medicine doctors help their patients in a variety of ways: they keep close records of their patient’s medical history; they evaluate patients to take preventative measures to maintain health; they screen their patients to determine if they have a disease or if they may be developing some type of condition that could negatively impact their lives; and they diagnose and treat patients when they become ill or are injured.

A Family Doctor is an asset that not only has the medical knowledge to treat your conditions, but also has a caring and established relationship with the members of your family.

Thanks for letting me know that family practice medicine focuses on caring for patients of any age. That sounds great because my children are all very different ages. I want to find a doctor to treat them all, so I’ll look for a good family practice.

Always wanted to know the exact information about the family practice. whenever it came across while reading i was always confused but thanks for the information.

Very well said no doubt rising a healthy family isn’t easy. It is important for you and your kids to have a healthy diet with a healthy lifestyle. The balance diet is one of the difficult battles for many working parents.