Recent research by Yale researchers Matthew Fisher, Mariel Goddu, and Frank Keil, posits that people think they know more than they actually do when they they have access to the internet. In their paper, published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, the researchers conducted a study in which one group was set up with access to the internet, the other without, and both groups answered a set of questions. When the groups answered a second, unrelated, set of questions, the online group were more confident that they knew the answers than the offline group.

Fisher remarked in an NPR article covering this study: “If we can’t accurately judge what we know, then who’s to say whether any of the decisions we make are well-informed?”

You may be saying you yourself, why is it a bad thing to search the internet for answers, especially if we know where to look? The researchers have answered, it’s not a bad thing — unless you can assure that people who need the information can always access the internet. In some situations, we want people to be truly knowledgeable.

When Should Physicians Be Truly Knowledgeable?

Fisher and his colleagues have pointed out that surgeons are one example of people you’d want to be truly knowledgeable — and it does seem logical that we’d want the people who presumably can’t use Google and hold a scalpel at the same time to have the information and skills in their own heads that they need to do their jobs. But what about general practitioners? We’ve heard from more than one physician in practice that looking things up on the web is a crucial part of their practice and even contributes to lifelong learning.

For these physicians, it may seem like the only situation where it’s impossible to turn to the internet for answers is the classic closed-book board exam — and many have made the point that a high-stakes exam is a poor judge of what people actually know. However, this new research shows that the knowledge you think you have might not really be in your head. Certainly, you can look up almost anything you need to know, but is there a danger that being able to access so much clinical knowledge is making physicians overconfident and unable to adequately judge what they should and shouldn’t search for? And, perhaps even more important, do physicians know what those gaps in their knowledge are?

There’s a general problem of overconfidence bias in medicine leading to medical errors and contributing to deficits in patient safety. A 2013 study in JAMA concluded, “Physician overconfidence is thought to be one of many contributing factors to diagnostic error and occurs when the relationship between accuracy and confidence is miscalibrated or misaligned such that confidence is higher than it should be.”

How to Find Out What You Truly Understand

Alex Djuricich, MD, Education Editor of NEJM Knowledge+, considers this issue of overconfidence bias in medicine to be of utmost importance. He also sees at least one possible solution to the problem: “NEJM Knowledge+ allows learners to state their confidence; thus, learners who are highly confident but answer incorrectly can quickly see that they need to temper this confidence with humility and self-reflection.”

We’ve written before about how NEJM Knowledge+ helps physicians to be more metacognitive, more aware of what they know and don’t know.

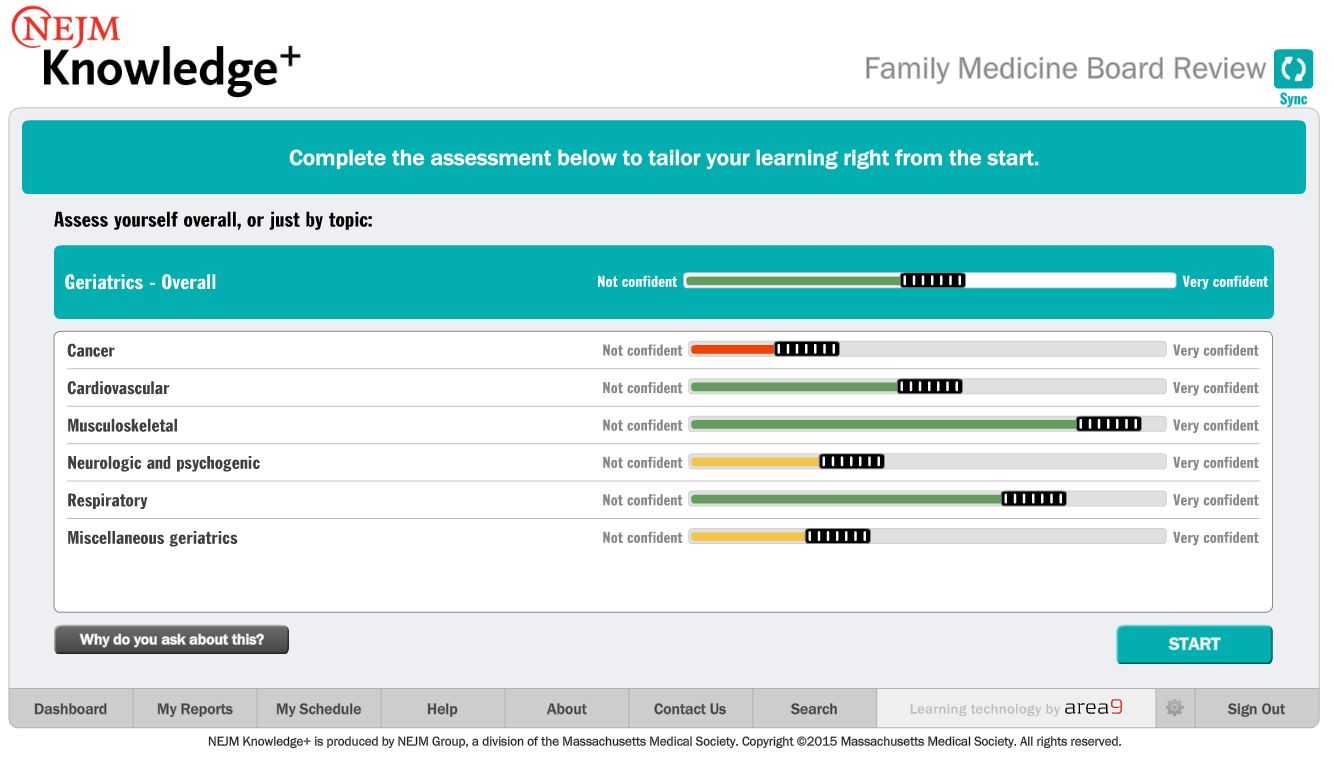

Setting Your Confidence Levels in Our Adaptive Program

Sliding the confidence slider down into the red zone will will prime our adaptive learning system to serve you multiple questions that support the same underlying learning objectives about the topics you have low confidence in, so that you may start to close that knowledge gap and overcome overconfidence bias.

As you answer the multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank questions, you’ll answer “how confident are you?” (these buttons submit your answer). Choosing your level of confidence requires you to think, however briefly, about your own knowledge. “Do I really know this?”

In addition, the system uses your confidence data to help determine which items you need to see again — often in the form of a slightly different question — to reinforce the metacognition and learning. So if you answer correctly but with low confidence, the algorithm will treat that like a wrong answer, and make sure to reinforce that learning.

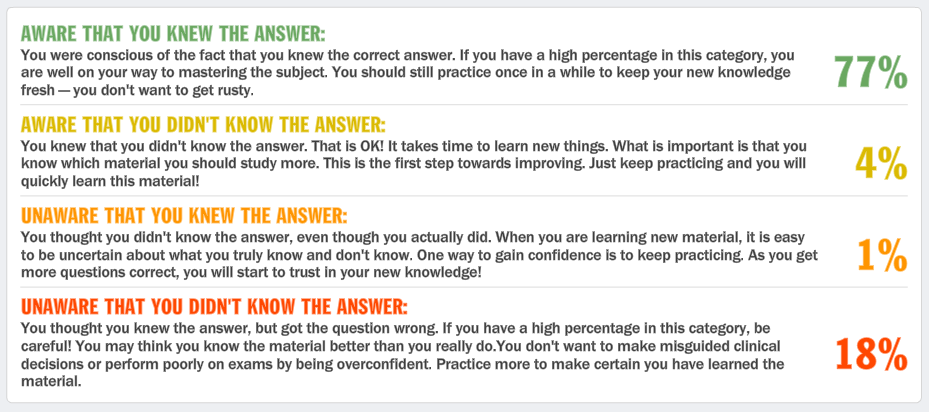

Reports Show Your Metacognitive Gaps

You’ll see how your confidence aligns (or does not align) with your performance in the reports. Try to avoid high percentages in the red zone: being unaware that you didn’t know the answer.

Can You (and Should You) Avoid Using the Internet While Testing Yourself?

Much of what you think you’ve memorized is actually something you’ve just read online — and some of what you find on the internet is outdated, contested, or simply wrong. Some skills and knowledge you know you have, and some you don’t know that you don’t know.

If you are being honest with yourself as you progress through self-assessments in various topics, you will start to become aware of the depth and breadth of your medical knowledge — and where your knowledge is shallow or narrow instead. You’ll stop thinking of the internet as a “cognitive prosthesis,” and think of it more as a crutch — one you’ll need to eventually walk without.

In an high-stakes board exam environment or in clinic or at the hospital seeing patients, where you are without access to search (or lacking the chutzpah to whip out your smartphone during a patient encounter!) you might suddenly realize that you don’t actually know what you thought you knew. If you’ve been using the internet, says the research, you are more likely to think you know the answers than you actually do.

It Is Possible to Overcome Overconfidence Bias in Medicine

As Fisher noted in an article at Harvard Business Review about his study, “The more we use the internet, the harder it will be to assess what people truly know. And that includes assessments about ourselves.”

However, if you become aware of your bias, you have a great chance of avoiding overconfidence. Try to work hard while in NEJM Knowledge+ and other learning tools to take note of this very human tendency toward overconfidence. Take advantage of the NEJM Knowledge+ reports showing you what you truly know and don’t know … and keep using Recharge to avoid memory decay.

What do you think about overconfidence bias in medicine? Have you noticed a tendency to be overconfident in your knowledge when you’re online? Do you feel strongly that physicians should have access to the internet all the time?

1) What do you think about overconfidence bias in medicine? My be dangerus for patients care

2) Have you noticed a tendency to be overconfident in your knowledge when you’re online? No

3) Do you feel strongly that physicians should have access to the internet all the time? Yes when is possible

As a matter of fact, the more I use the internet, the more Ἓν οἶδα ὅτι οὐδὲν οἶδα”.

Formulating the right questions is critical in finding the answers and originates between your ears.